The halls of Congress

were awash with rumor in the Summer of 1918... They would have been surprised indeed if they could have found any of the ammunition for the new pistol, had an opportunity to dissect it and been shown the fact sheet - perhaps even impressed! It seems that the new cartridge for the .30 caliber pistol utilized an 80 grain projectile launched by 3 1/2 grains of Bullseye Powder. This tiny pill left the muzzle of its intended weapon at 1300 feet per second, could reliably hit a man-sized target at 350 yards and would kill, given a good hit, as far out as 500 yards. Not bad for a handgun! The fly in the ointment was that this pistol looked like nothing ever before seen and was held in strictest secrecy. While the U.S. Pistol, Caliber .30 M1918 functioned like a blowback pistol, shooting what appeared to be an extra long .32 ACP round, there all resemblance ended. Much as Winston Churchill named the first armored vehicles to fight in WWI "Water Tanks" to conceal their identity and purpose, so it was with our new “pistol”. When John Pedersen appeared in Washington in 1917 and asked that he be allowed to conduct a secret demonstration, the request was readily granted. Mr. Pedersen’s considerable reputation as an arms designer had preceded him. A collection of Generals and Ordnance Department Brass assembled at the Congress Heights Range Facility in Washington D.C.

Although the demonstration started in a rather mundane way, the witnesses were destined to leave with their mouths open! To kick off the festivities, Mr. Pedersen fired several shots from a conventional looking M1903 Springfield Rifle in the normal bolt action fashion. He then produced a peculiar looking device, removed the standard bolt, and inserted the device into the M1903 bolt recess. He then proceeded to fire a tremendous number of rounds downrange in what seemed to be a very short period of time. To those observing the demonstration, it almost appeared he had converted the Springfield to a one-man machine gun! Even though the device was only semi-automatic, no one had ever seen a conventional rifle fired so rapidly. They were impressed! An immediate secret classification was slapped on Mr. Pedersen's invention. To deceive the enemy, the Ordnance Department decided to call it The U.S. Automatic Pistol, Caliber .30, Model of 1918! The mysterious "Pedersen Device", designed to give the Allies the upper hand during the big spring offensive of 1919 had been born... The information of the existence of such a weapon was flashed in code to no less a person than General John J. Pershing. At his direction, an Ordnance Captain was sworn to secrecy and dispatched to France to demonstrate our first prototype semi-automatic rifle. The demonstration took place in December of 1917 and General Pershing was more than impressed. He ordered 100,000 of the devices with appropriately modified M1903 Springfield Rifles to be delivered to France at the earliest possible moment. Remington went into production started production of the Devices in early 1918. By now Remington was well into the production of the Pattern 17 Enfield. Plans were also made to do a feasibility study as to whether a similar device could be made to function in the M1917 Enfield and the Russian Mosin-Nagant. A tool room model of the Device for the M1917 Enfield was demonstrated in August 1918 and designated the M1917 Mark II. A photograph also exists of at least one tool room model of a Pedersen Device for the Mosin-Nagant. Word was dispatched to General Pershing by courier that a total of 500,000 rifles and Devices (a combination of both Springfields and Enfields) could be ready for the 1919 Spring Offensive. Since the war ended just over two months after General Pershing received the word, no production was initiated on the Enfield version. Production of the Springfield Pederson Device(s) was halted at the end of February 1919 with a total of 65,000 Devices having been produced. Strangely, the production of the specially designed M1903 Rifle was not begun until 2 December 1918; almost a month after the Armistice had been signed. Production of the Mark

I Rifle

continued until the fall of 1920. Total production figures of the Mark

I M1903 indicate that a total of

101,7 75 rifles were produced. The question is, how

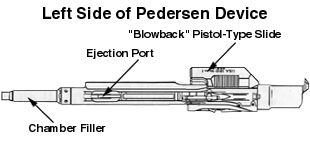

much of a job was it to convert In order to make such an invention practical, it had to function in a service rifle, and be readily converted back and forth to ensure that the infantryman had access to both long range, accurate and powerful ammunition (.30-'06) and the smaller rapid fire cartridge. Since the Pedersen Cartridge was little more than a longer version of the .32 ACP Cartridge (which is actually a .30 caliber), it would have obviously rattled around in the .30-’06 Chamber. This “slight problem” was solved by using a chamber filler that was part of the Device and was rifled with ten shallow lands and grooves. The chamber filler had a much smaller pistol cartridge chamber that mated with the firing pin and extractor of the device itself. When the cartridge was fired, the “lump” on the rear of the device acted as the equivalent of a pistol slide. The slide’s weight allowed the device to function like a blowback pistol.. The empty cartridge case was ejected through the ejection port in the side of the device (see illustration of the left hand side of the Device below), which was designed to be aligned with the ejection port milled into the side of the Mark I Springfield Receiver.

The Pedersen magazines easily snapped in and out of the receiver with one hand, and held 40 rounds each. When firing the rifle with the Device in place, the magazine stuck out of the right side of the receiver at a 45°, and the rifle was fired in a conventional fashion. The tests conducted to approve the production version of the Device and the Mark I were carried out by both shooters and target-pullers all sworn to strictest secrecy. The target-pullers were totally in the dark about what sort of weapon they were marking targets for, and the shooters were not allowed to speak to those pulling and marking targets in the butts. The rifles were manufactured by Springfield Armory starting with serial number 1,034,502, but reportedly, the serial numbers were intermingled with the standard Springfield production, so no definitive serial number range can be discerned. The Devices themselves were manufactured by Remington-UMC at their Bridgeport, Connecticut plant. An

evolution in tactics By 1931 the Pedersen Device was declared obsolete and ordered destroyed in April of that year.. The Secret classification of the Pedersen had been downgraded to Confidential on 17 December 1919, where it remained until their destruction in 1931. The Mark I Rifles remained in storage until 1937-1938 when they were restored to the standard M1903 configuration by replacing the tripper sear and Magazine Cut Off with the standard versions and reinstalling their standard bolts. Thus the Mark I was returned to service. The ejection port, far from weakening the receiver was judged to provide additional gas relief in the event of an overload or pierced primer. All Mark I receivers were of the double heat treated variety, thus assuming correct headspace, the Mark I Springfield is an extremely safe rifle to shoot. There are several versions of the destruction of the Devices themselves, but the most prevalent is that they were burned at Benicia Arsenal in California by pouring gasoline over them and their magazines and simply torching them off. This version receives some validity due to an occasional magazine or even a Device itself that will appear with obvious fire scale over all or most of their bodies. There are precious few of the Devices remaining, as only a small number of the devices were saved for posterity. One may be seen at each of the following museums: The Smithsonian, Springfield Armory Museum, the Marine Corps Museum, the Armor Museum at Ft. Knox, the West Point Museum and at least one at the Remington Museum (presumably along with tool room models of the Pedersen Device designed for the Enfield and the Mosin-Nagant). While several Devices are known to be in private collections, the grand total of surviving pristine Devices is probably in the neighborhood of between 25 and 30, although there may be more. At least one was found in the German Ordnance Collection at the conclusion of WWII, although the German specimen may well be one of those currently residing in the Museums listed above. The presence of a copy in the German Collection would seem to indicate that our effort to keep the Pedersen Device classified was all for naught, unless of course, they acquired their copy after the Devices had become obsolete and supposedly destroyed. Even though the Pedersen Devices themselves are scarce, such is not the case with the Mark I Springfield. While considerably rarer than the standard M1903, many of the remaining Mark Is were later sold through the DCM sales program following WWII. Because of the relative lack of publicity of the Device and its companion, the Mark I M1903, the recipients were often at a loss as to what they had acquired. An article written in the American Rifleman in 1932 by then Major Julian Hatcher had explained our secret weapon of WWI, but apparently few took note. The Mark I and the Pedersen Device remained largely an enigma until the mid to late 1950s when they started to appear in steadily increasing numbers. The recent lottery conducted by the Civilian Marksmanship Program specifically allowed the potential buyer to request a Mark I. For those of you lucky enough to be drawn for the elusive Mark I, be assured that you have acquired one of the most interesting pieces of U.S. Ordnance History ever produced by Springfield Armory – the unique companion piece of the “The Pipsqueak Pistol That Never Was”...

|

It seems that a bit of Secret information had inadvertently fallen into

the hands of some Washington Officials. The United States was adopting a

new pistol! Why in the world would we do THAT??

It seems that a bit of Secret information had inadvertently fallen into

the hands of some Washington Officials. The United States was adopting a

new pistol! Why in the world would we do THAT?? ecret demonstration, the request was readily granted. Mr. Pedersen’s

considerable reputation as an arms designer had preceded him. A

collection of Generals and Ordnance Department Brass assembled at the

Congress Heights Range Facility in Washington D.C.

ecret demonstration, the request was readily granted. Mr. Pedersen’s

considerable reputation as an arms designer had preceded him. A

collection of Generals and Ordnance Department Brass assembled at the

Congress Heights Range Facility in Washington D.C.

the M1903 bolt action Springfield into a semi-automatic, and just how

was it accomplished? The answer is simple, even if the solution was not.

Mr. Pedersen made very few modifications to the existing M1903

Springfield. Because it was necessary to mount the device into the

receiver of the rifle itself, an ejection port had to be cut into the

left side of the receiver and the sear mechanism of the ‘03 had to be

modified to release the firing pin of the Device once the trigger was

pulled. The specially modified receiver had a long oval slot milled into

its left side to act as an ejection port, matching the ejection port of

the Device. The specially modified receiver was given the nomenclature

of

the M1903 bolt action Springfield into a semi-automatic, and just how

was it accomplished? The answer is simple, even if the solution was not.

Mr. Pedersen made very few modifications to the existing M1903

Springfield. Because it was necessary to mount the device into the

receiver of the rifle itself, an ejection port had to be cut into the

left side of the receiver and the sear mechanism of the ‘03 had to be

modified to release the firing pin of the Device once the trigger was

pulled. The specially modified receiver had a long oval slot milled into

its left side to act as an ejection port, matching the ejection port of

the Device. The specially modified receiver was given the nomenclature

of  The

device itself was held into the action utilizing a specially designed

Magazine Cut Off, and the sear of the Pedersen Device was triggered by a

special “tripper sear” that replaced the normal sear of a standard

M1903 Rifle. The “tripper sear” would function with either the M1903

utilizing the standard bolt or with the Pedersen Device in place. All

that was required to interchange the standard bolt with the device or

vice versa, was to put the Magazine Cut Off in the center position,

remove the standard ’03 Bolt in the normal fashion. The device could

then be rapidly inserted in its place, being sure to rotate the Cut Off

back into its normal position. With a little practice the bolt - device

exchange was extremely fast and easy to accomplish.

The

device itself was held into the action utilizing a specially designed

Magazine Cut Off, and the sear of the Pedersen Device was triggered by a

special “tripper sear” that replaced the normal sear of a standard

M1903 Rifle. The “tripper sear” would function with either the M1903

utilizing the standard bolt or with the Pedersen Device in place. All

that was required to interchange the standard bolt with the device or

vice versa, was to put the Magazine Cut Off in the center position,

remove the standard ’03 Bolt in the normal fashion. The device could

then be rapidly inserted in its place, being sure to rotate the Cut Off

back into its normal position. With a little practice the bolt - device

exchange was extremely fast and easy to accomplish. It

was envisioned that the Doughboy would carry his normal cartridge belt

holding 100 rounds of .30-’06 ammunition, and two web magazine pouches

holding five 40 round Pedersen Magazines each for a total of 400 rounds

of Pedersen Ammunition. The Cartridge Belt would be further festooned

with a metal can designed to carry the Device when using the .30-’06

bolt, and a cloth pouch to carry the bolt when using the Device.

It

was envisioned that the Doughboy would carry his normal cartridge belt

holding 100 rounds of .30-’06 ammunition, and two web magazine pouches

holding five 40 round Pedersen Magazines each for a total of 400 rounds

of Pedersen Ammunition. The Cartridge Belt would be further festooned

with a metal can designed to carry the Device when using the .30-’06

bolt, and a cloth pouch to carry the bolt when using the Device. began to emerge in the 1920s that seemed to indicate that the static

trench warfare was a thing of the past. In light of the new thrust of

infantry tactics, the pipsqueak cartridge fired by the Pedersen Device

would be of little use in a fluid Infantry environment, especially

against aircraft or armored vehicles. The projectile fired by the

Pedersen cartridge lacked the ominous “crack” caused by the

.30-’06 bullet breaking the sound barrier – a sound judged to be

unnerving to our enemies on the battle field.

began to emerge in the 1920s that seemed to indicate that the static

trench warfare was a thing of the past. In light of the new thrust of

infantry tactics, the pipsqueak cartridge fired by the Pedersen Device

would be of little use in a fluid Infantry environment, especially

against aircraft or armored vehicles. The projectile fired by the

Pedersen cartridge lacked the ominous “crack” caused by the

.30-’06 bullet breaking the sound barrier – a sound judged to be

unnerving to our enemies on the battle field.